Alouestes – Stage 3 : In the wake of the great fires

On May 3rd, 2023, Tiphaine and her travelling companion Glen, landed in Anchorage, Alaska, 7,500 kilometres west – or Alouestes – of France.

Since then, they have been cycling between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Ocean, heading south towards a destination that is still unknown. From stage to stage, the duo stopped at breathtaking places, well preserved or, instead, threatened by human activities. From the frozen ground in the Yukon Valley (Canada), to the immense wheat field that seems to be Washington State (USA) at first glance, via the glaciers and forests of British Columbia (Canada), Tiphaine and Glen’s journey is not just a human adventure, but also a scientific one.

In this third episode of Alouestes, quoi de nouveau ?, two scientists, Karen Hodges, biologist and conservation ecologist at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna (Canada) and Juan Cuesta, physics researcher at the Laboratoire Interuniversitaire des Systèmes Atmosphériques (LISA-IPSL), take a look back at a fiery summer in North America.

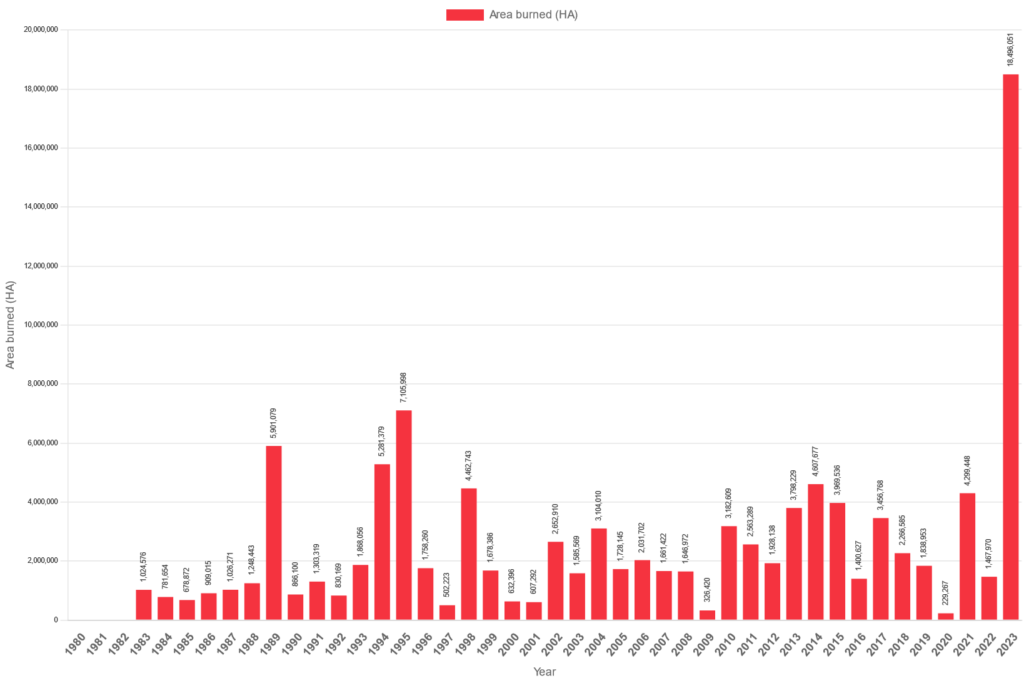

Fires devastated 18,500,000 hectares of Canadian forest in 2023.

This is the staggering figure released by the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC): slightly more than the entire French forest area (Source: Inventaire forestier 2022).

While wildfires are nothing new, what’s striking today is their intensity and size: «The problem, in recent years, is that we’re seeing much larger and much more severe fires, in terms of surface area burnt and intensity» says Karen Hodges, who worked on wildfires for more than twenty years.

Annual area burnt in Canada, between 1980 and 2023. Source : Ciffc.

The reasons behind this escalation in fires are directly linked to human management of the forests, as well as changing climatic conditions. «We are reaping what we have sown over decades, in terms of forestry, says the Canadian biologist. People have suppressed forest fires, so a large number of small fires, which could have occurred over decades, have not taken place. As a result, these areas have accumulated more and more fuel. And, because we have replanted mainly monocultures, made up of a single species and relatively dense, all this has become an extraordinarily connected fuel. The other factor is the “fire climate”: the combination of heat and drought. If a fire breaks out, the fuel will be very hot and dry. »

Burnt ecosystems take several decades to recover, because fires degrade water quality, amplify erosion and threaten a forest’s ability to regenerate. And other consequences are felt thousands of miles away.

«The smoke rises and, depending on the height reached, it will disperse and be carried by the wind. If these layers of smoke come down, they can affect air quality, as we saw this summer in Chicago or in New York», explains Juan Cuesta, a specialist in smoke and its effects on the atmosphere.

Riding her bike, Tiphaine travelled along the scars left by the great fires that have ravaged the West Coast of North America in recent years.

Photo Gallery

In the Canadian Rockies: old forest fires west of Swift River, Yukon. The 27th of May, 2023. © T.Claveau

This is a classic example of how variable a fire is when it burns: the really dark black patches, are places where the fire burnt more severely. The red patches, show threes that didn’t survived the fire, but they didn’t fully burn, so you still have a bunch of needles on those threes. The green patches at the center of the picture : here, clearly something happened, so that the fire didn’t burn into that valley. That will be an important residual forest, that wildlife and animals could use, until the landscape starts regenerating into useful habitat. This patchy pattern is quiet common with big fires.

– K. Hodges

In 2010 and 2011, two huge forest fires transformed the landscape around the Stewart-Cassiar highway in British Columbia. The fires grew rapidly, fuelled by strong winds, a hot, dry season and the fuel present: black spruce. © T.Claveau

This is something fire scientists are very nervous about. Every standing snag here, is fuel. If you look at the forest floor here, we’ve got down trees and this regenerating material, shrubs and young trees, are also flammable. This area could easily reburn. The living fuels are wetter, because the plant bodies contain water, but all these dead standing snags are dry fuels. There is a real risk of burning more material than the initial burn.

– K. Hodges

In the summer of 2023, a forest fire broke out on the edge of the village of McBride in British Columbia. Photos taken on June, 23rd, a few weeks after the fire. © T.Claveau

The pattern of what has burnt and what not, can sometimes be natural, sometimes it is driven by the firefighters’ efforts. I’m sure that the firefighters would have been very active on the side of the fire burning towards the town.

– K. Hodges

The smoke rises according to the heat released. It’s a mixing and stirring effect, called pyroconvection: the fire heats the air and this air, warmer than the surrounding environment, moves and tends to ascend.

– J. Cuesta

Fireweed is the emblem of the Yukon and is known as the first plant to emerge from the ashes. © T.Claveau

Some plants can resprout, the fire doesn’t kill all the roots. Other plants are great at seed dispersal, and fireweed would be on of that one. They just love newly disturbed, sunny environments, so that they can seed everywhere. It is an adaptive strategy.

– K. Hodges

Forest fires and revival east of Jasper, Alberta. Fires are an integral part of the forest cycle, restoring nutrients to the soil, facilitating the growth of young plants and attracting a variety of wildlife. © T.Claveau

There are other species that also have this strategy. Even the conifers. Some of them have cones covered with a thick layer of wax: the heat opens them and the new seeds do really well. Serotiny cones are good examples of that.

– K. Hodges

Coos Bay, Oregon, USA, 9th of August 2023. In Canada and the United States, forest fire prevention is essential because human activities (camping, cigarette butts, etc.) are important ignition causes. © T.Claveau

Smokey bear is immensely well known but very misleading, because that campaign focused on human ignition of wildfires. Many fires are caused by lightning strikes, and there are so many other things that we do, that affect how, when and where a fire burns, that focusing on human ignition is really misleading, in terms of what we experienced in the last years with this record numbers of fire. This character is immensely popular, it has its own ZIP code for mails, but the legacy of this successful advertising campaign is really negative.

– K. Hodges

Redwood National Park, California, the 13th of August, 2023. This Redwood is burnt inside, probably caused by lightning. This is a common cause of forest fires. © T.Claveau

In general, the spark in these areas is lightning. Fires spread several kilometres a day, burning an enormous amount of fuel. Fires are sporadic events that are difficult to model and predict, so it’s hard to incorporate them into climate models.

– J. Cuesta

Yosemite National Park, California, the 28th of August, 2023. Forest fires are an important process in the forest cycle, and forest management teams have now reintegrated, finely controlled, fires into the life of the forest, even in places as popular with tourists as Yosemite Valley or Mariposa Grove. © T.Claveau

These trees very rarely burn. Coastal forests are huge amounts of fuel, these are some of the most productive, green, huge crops of biomass. It is an immense fuel load; however, it is wet. Those years, when those threes burnt, there was an exceptional drought and we were getting winds off the mountains, pushing moisture off-shore, rather than drying it from the coast on. And then the ignition happened.

– K. Hodges

A burnt giant sequoia, from the inside. © T.Claveau

Many animals die, other flee, other stay in the area of the fire and seek up shelter, that can be on the top of the tree, underground, in water bodies… Some animals are attracted to postfire conditions, like some beetles that consume the dead trees. Woodpeckers would come and eat the beetles, and enjoy nesting in the trees.

– K. Hodges

Find out more

The first part of Alouestes, Étape 1 : Les sols en dégel entre l’Alaska et le Canada, with scientist Antoine Séjourné.

The second part of Alouestes – Étape 2 : La grande fonte des glaciers nord-américains, with glaciologist Etienne Berthier.

Follow Tiphaine & Glen’s path on Instagram or take a look at their travel blog Alouestes !