Exoplanets’ climate – it takes nothing to switch from habitable to hell

The Earth is a wonderful pale blue and green dot covered with oceans and life, while Venus is a yellowish sterile sphere that is not only inhospitable but also sterile. However, the difference between the two bears to only a few degrees in temperature.

A team of astronomers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), with the support of the CNRS laboratories of Paris (LMD, IPSL) and Bordeaux (LAB), has achieved a world’s first by managing to simulate entirely the runaway greenhouse process which can transform the climate of a planet from idyllic and perfect for life, to a place more than harsh and hostile.

The scientists have also demonstrated that from initial stages of the process, the atmospheric structure and cloud coverage undergo significant changes, leading to an almost-unstoppable and very complicated to reverse runaway greenhouse effect. On Earth, a global average temperature rise of just a few tens of degrees, subsequent to a slight but unavoidable rise of the Sun’s luminosity, would be sufficient to initiate this phenomenon and to make our planet inhabitable.

The idea of a runaway of the greenhouse effect is not new. In this scenario, a planet can evolve from a temperate state like on Earth to a true hell, with surface temperatures above 1000°C. The cause? Water vapor, a natural greenhouse gas. Water vapor prevents the solar irradiation absorbed by Earth to be reemitted towards the void of space, as thermal radiation. So, it traps heat a bit like a rescue blanket. A dash of greenhouse effect is useful – without it, Earth would have an average temperature below the freezing point of water, looking like a white ball covered with ice and hostile to life.

On the opposite, too much greenhouse effect increases the evaporation of oceans, and thus the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere. “There is a critical threshold for this amount of water vapor, beyond which the planet cannot cool down anymore. From there, everything gets carried away until the oceans end up getting fully evaporated and the temperature reaches several hundred degrees,” explains Guillaume Chaverot, former postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Astronomy at the UNIGE Faculty of Science and main author of the study.

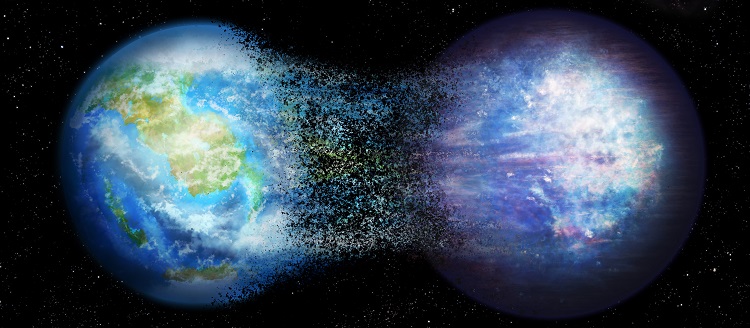

Runaway greenhouse effect can transform a temperate habitable planet with surface liquid water ocean into a hot steam dominated planet hostile to any life. © Thibaut Roger / UNIGE

World premiere

“Until now, other key studies in climatology have focused solely on either the temperate state before the runaway, or either the inhabitable state post-runaway,” reveals Martin Turbet, CNRS scientist in Paris and Bordeaux laboratories (LMD, IPSL, LAB), and co-author of the study. “It is the first time a team has studied the transition itself with a 3D global climate model, and has checked how the climate and the atmosphere evolve during that process.”

One of the key points of the study describes the appearance of a very peculiar cloud pattern, increasing the runaway effect, and making the process irreversible. “From the start of the transition, we can observe some very dense clouds developing in the high atmosphere. Actually, the latter does not display anymore the temperature inversion characteristic of the Earth atmosphere and separating its two main layers: the troposphere and the stratosphere. The structure of the atmosphere is deeply altered,” points out Guillaume Chaverot.

Serious consequences for the search of life elsewhere

This discovery is a key feature for the study of climate on other planets, and in particular on exoplanets – planets orbiting other stars than the Sun. “By studying the climate on other planets, one of our strongest motivations is to determine their potential to host life,” indicates Émeline Bolmont, assistant professor and director of the UNIGE Life in the Universe Center (LUC), and co-author of the study.

The LUC leads state-of-the-art interdisciplinary research projects regarding the origins of life on Earth, and the quest for life elsewhere in our solar system and beyond, in exoplanetary systems. “After the previous studies, we suspected already the existence of a water vapor threshold, but the appearance of this cloud pattern is a real surprise!” discloses Émeline Bolmont. “We have also studied in parallel how this cloud pattern could create a specific signature, or ‘fingerprint’, detectable when observing exoplanet atmospheres. The upcoming generation of instruments should be able to detect it,” unveils Martin Turbet. The team is also not aiming to stop there, Guillaume Chaverot having indeed received a research grant to continue this study at Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG). This new step of the research project will focus on the specific case of the Earth.

A planet Earth in a fragile equilibrium

With those new climate models, the scientists have calculated that a slight increase in the Sun’s luminosity (within 1 billion years) – leading to an increase of the global Earth temperature, of only a few tens of degrees – would be enough to trigger the irreversible runaway process on Earth and make our planet as inhospitable as Venus.

One of today’s climate challenges is to succeed in limiting the average warming on Earth, resulting from greenhouse gas emissions, to only 1.5 degrees by 2050. The main question of Guillaume Chaverot’s next research grant is to determine whether or not a significant increase in greenhouse gas emissions could kickstart this runaway process as a slight increase of the Sun luminosity might do.

The Earth is thus not so far from this apocalyptical scenario. “Assuming this runaway process would be started on Earth, an evaporation of only 10 meters of the oceans’ surface would lead to a 1 bar increase of the atmospheric pressure at ground level. In just a few hundred years, we would reach a ground temperature of over 500°C. Later, we would even reach 273 bars of surface pressure and temperatures above 1000°C, when all the oceans would end up totally evaporated,” concludes Guillaume Chaverot.

More

Reference

Guillaume Chaverot, Emeline Bolmont and Martin Turbet. First exploration of the runaway greenhouse transition with a 3D General Circulation Model. Astronomy & Astrophysics. Volume 680, December 2023. DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202346936

https://www.aanda.org/component/article?access=doi&doi=10.1051/0004-6361/202346936

Contacts

- Martin Turbet, Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique (LMD-IPSL) & Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux •

- Guillaume Chaverot, Département d’astronomie Faculté des sciences UNIGE, Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble •

- Émeline Bolmont, Département d’astronomie Faculté des sciences UNIGE, Centre pour la Vie dans l’Univers •

Source : Université de Genève.